Chronology

1929

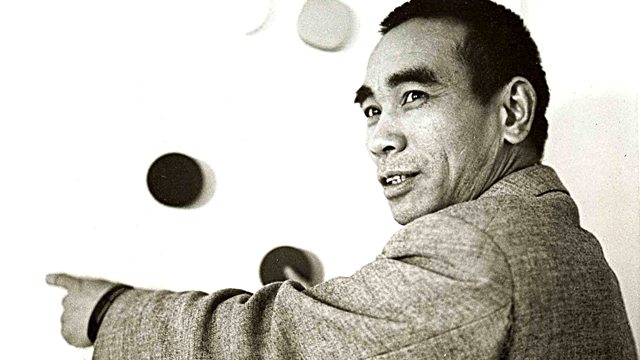

Li is born on 6 April in Hsu village, near Lu Shan, Kwangsi Province, China. He is the eldest son in a peasant family.

c. 1940

At the age of ten or eleven, Li’s parents give him up for adoption to his aunt and her husband. His mother’s brother-in-law is a high-ranking officer in the army of the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. This soldier is killed early in the Sino-Japanese war and Li is sent to a succession of orphanages and schools for children of bereaved Nationalist officer-families, where he passes the rest of his childhood and adolescence.

1948

Not having had an education as a child, Li is eventually able to study at a special school for the children of Chang Kai-shek’s officers in China.

1949

After their defeat by the Communist forces led by Mao Tse-tung, the Nationalists retreat to Taiwan. Li goes as part of this exodus and arrives in Taiwan together with the other students of special schools.

1951

Li enters the art education department of Taipei Normal College for teacher-training. He meets Hsiao Chin and Ho Kan, who are fellow students and also refugees from mainland China.

1952

Dissatisfied with the conservative and academic training in Chinese art and aesthetics prevailing in the school, Li, along with Hsiao Chin, Ho Kan and others, studies with the artist and independent teacher Li Chung-sheng, who exerts a decisive, liberating influence on many young Taiwanese artists. Having studied in Japan, he is well versed in European as well as traditional Chinese modern painting. He emphasises the importance of developing a co-ordination between hand, mind and eye through drawing, but he also, in Hsiao Chin’s words, ‘encouraged each one of us to fully exploit our own characteristics and personality’. Li makes his first abstract work.

1955

After graduating from Taipei Normal College, Li does military training in the course of which he learns mathematics and electrical engineering. Later he uses mathematical equations to title paintings, disregarding mathematical logic in favour of what appears to be a personal (but unexplained) coded meaning.

1956

With Hsiao Chin, Ho Kan, Yan Hsia, Wu Hao, Chen Tao-ming, Hsiao, Ming-hsien and Ouyang Wen-yuan (all ex-students of Li Chung-sheng), Li establishes of the Ton Fan Painting Group. Ton Fan produces what are thought to be the first abstract works in modern China. Of the drawings and watercolours he produced between 1956 and 1958, Li wrote later, ‘I was influenced by the basic ideas of the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu and by Chinese calligraphy, in the colours I tried to recapture the special quality of Chinese porcelain and ancient cave paintings.’

1957

Li is invited, with Ton Fan, to exhibit at the 4th São Paulo Bienal, Brazil.

1959

According to his own account, Li originates the idea of the Point. ‘In 1959 my first painting was a tiny black dot on a white square of canvas – nothing could be simpler than that.’

1961

Hsiao Chin, who has been travelling extensively in Europe and sending back reports of new developments in art to artist friends and newspapers in Taiwan, settles in Milan. There he establishes Il Punto (The Point) group with the Italian painter Antonio Calderara and the Japanese sculptor Kengiro Azuma. Hsiao Chin invites artists from Ton Fan to join him in Milan and several (including Li) do. Later, Spanish, French and Dutch artists joint the movement. The Italian artists Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni are also in close contact.

1962

Li arrives in Italy in late 1962 or early 1963. After a short stay he travels to Bologna and settles there. The Bolognese furniture designer and patron of the arts Dino Gavina has admired Li’s work for some time. He helps Li to obtain the necessary papers to settle in Italy and offers him a studio and bedroom in his furniture factory at San Lazzaro, Bologna. Li remains in San Lazzaro for four years. There he produces his series of folding painting books, and numerous paintings in which he evolves the pictorial form of the tiny Point, or Points, in a monochrome field. He sometimes glues small strips or patches to the canvas, overpainted white so that they form very low reliefs, and from these progresses to wood, and sometimes metal, reliefs of raised panels. He restricts his palette to four colours – black, red, white and gold – to each of which he gives a primordial symbolic value. His links with the newest tendencies in European art – kinetics, monochrome paintings, ‘all over’ composition – is underscored by his inclusion among Italian, Dutch, German and Latin American artists in the Rotterdam exhibition anno 62.

1965

Li is invited by David Medalla and Paul Keeler to show his work at Signals in London, where he participates in Soundings Two, an international survey of experimental art. The White Book, a boxed set of embossed prints, is published in Bologna in an edition of 100 copies, with a preface by Murilo Mendes and an explanatory key provided by the artist.

1966

Keeler and Anthony de Kerdrel organise at Signals 3 + 1, an exhibition which includes Li, Hsiao Chin, Ho Kan, and the Italian artist Pia Pizzo. Li travels to London and is commissioned by Medalla to execute a large wall relief incorporating points especially for the show which was subsequently lost.

He decides to stay on in London and rents a room, first in James Street, near the gallery, and later in Shroton Street, Marylebone. Works part-time for the furniture designer Zeev Aram at Aram’s showroom in King’s Road, Chelsea; Aram becomes a friend and collector of Li’s work.

Li begins, almost immediately, to write in English, continuing a habit of producing short, succinct poems. Li teaches himself photography and takes many pictures in the streets and parks of London. Some are printed in a circular form and included in his reliefs. He meets the Brazilian artist Mira Schendel during her exhibition at Signals. They exchange works and begin a correspondence after Schendel returns to São Paulo.

1967

Li stages the All & Nothing Show at Speakers’ Corner, Hyde Park. As a result of recommendations from David Medalla, Li is invited by Nicholas Logsdail to exhibit at the new Lisson Gallery and he forms an association with the gallery.

His first show Cosmic Point opens at the Lisson. To accompany this show, the first of Li’s distinctive small square catalogues appear. As well as photographs, it contains four ‘multiples’ with a single Point set on a white page, poems, by Li, and a poem and prose ‘meditation’ dedicated to Li by David Medalla.

1968

Li leaves London and moves to Cumberland. He settles at Boothby, in a large room made available by his friend Nick Sawyer and Nick’s stepfather Wilfrid Roberts. In October he holds a studio exhibition of his new work there. He becomes increasingly interested in manipulable, participatory structures. He invents the moveable, magnetic point, which, with the aid of a drawing pin, can be placed anywhere on the walls of a room in any composition: ‘If you ask me where my art is going after today, my answer is “Toyart”, which means: my works seem like “toy” – good for everyone, form children to old men (women)’. Li’s second show Cosmic Multiples opens at the Lisson Gallery, (it features the Cosmagnetic Multiple, a mass-produced metal panel and four magnetic points, red, white, gold and black, selling at the gallery for nine pounds).

He participates in Su Braden’s democratic art scheme, Pavilions in the Parks in London. The scheme is a set of polyhedral shelters in London parks during the summer to give artists an opportunity to show their work. Works are selected by random from a list of applicants.

1969

Golden Moon Show opens at the Lisson Gallery, Li’s last exhibition there (it coincides with the voyage of Apollo 11 to the moon). The installation consists of three distinct environments: ‘Man on the moon = men in the stars’, ‘Life station’ and ‘Universe = one’. The catalogue introduction is written by Nicholas Logsdail. Reviewing the exhibition in Architectural Designs, Jasia Reichardt compared the atmosphere of Li’s exhibition to Brancusi’s studio in the 1920s: ‘Li’s “points”, and there is a considerable number of different ones, have the universality of Brancusi’s (endless) column. Both the column and the point are the expression o fan aspiration and an embodiment of a spiritual attitude.’ Reichardt goes on to speak of the ‘artless and uncontrived’ quality of Li’s exhibition, and comments that it is Li’s poems, rather than photographic reproductions, which best conveys the flavour of what he says in his art work.

1970

Li builds an environmental and participatory work for the Little Missenden Festival in Buckinghamshire.

1971

Li participates in Pioneers of Participation Art curated by Rupert Legge and mark Powell-Jones at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford. Other artist included are Lygia Clark, John Dugger, David Medalla and Graham Stevens.

1972-1982

Li buys a small, run-down farmhouse at Banks on Hadrian’s Wall from the painter Winifred Nicholson who lives nearby and with whom he becomes friends. After moving in and refurbishing the building single-handedly, he opens it to the public in August 1972 as the LYC Museum & Art Gallery (LYC).

For the next ten years, he puts almost all his energy into building, equipping and running the gallery, publishing catalogues and books, and giving his attention to other artists. There is little time for his own art work, although he makes moveable magnetic ‘alphabet’ Points for the children’s art room and continues to experiment with photography. (See the special section in this publication on the history of the LYC Museum).

1983

With the closure of LYC, Li’s relationship with official arts funding bodies such as Northern Arts ceases. This, and his desire to travel after being permanently tied to LYC for ten years (in spite of the urgings of friends, he never took a holiday), make him decide to put the majority of the building up for sale. Knowing nothing of English law, he is taken advantage of by a prospective ‘purchaser’ who moves into part of the property, refuses to buy, to leave, or to pay more than a small amount in rent. Being a house-owner Li is unable to claim benefit, therefore is unable to pay his taxes, bills or the solicitors’ fees. The next seven years (until the ‘lodger’ finally leaves after vandalising part of the property) are spent in an exhausting and frustrating struggle to get his case understood by the authorities, an ordeal which left his health permanently damaged.

1986-1987

Li makes one or two trips to visit friends and spends three months in Spain.

1989

Despite his trials, Li’s art work continues to develop. He is invited to participate in The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Postwar Britain, a survey show of twenty-four artists curated by Rasheed Araeen (Hayward Gallery, London; Wolverhampton Art Gallery; and Manchester City Art Gallery, 1989-1990), where he brings several strands of his work to fruition.

His room contains twelve free hanging discs supporting a large number of photographic magnetic points for the public to move (up to 350 in all), Mushroom Toys (low tables with moveable points), and Time Toys, reliefs incorporating the intermittent chimes from dismantled clocks. Writing in the catalogue, Rasheed Araeen frames Li’s work, and that of the other artists in the show, within ‘the process of decolonisation across the world’. He pays tribute to these artists who ‘defied their “otherness” and entered the modern space that was forbidden to them.’ The significance of Li’s work, in Araeen’s opinion, was not merely its “fusion” between his own culture and Modernism but its strategic location within the avantgarde tradition”. Although ‘without any rhetoric of opposition, it is metaphorized paradigmatically. There is no concern for painterly marks or sculptural modulations. Instead the various elements of the work are placed either on the flat surface or hung in space, not necessarily in a fixed position but so they can be constantly shifted in a variety of arrangements manipulated by the spectator or audience. Demystification is achieved not only within the work itself but also by changing the status of the work from a single unique object to multiples.’ According to Andrew Dempsey, Hayward Gallery Assistant Director at the time, Li Yuan-chia’s and David Medalla’s rooms in The Other Story are those in which people ‘linger most’.

1990

At this stage in his life Li makes a devastating personal discovery: that his mother was not the person he always thought she was, but another, and his real mother is still alive. Hearing that she is poor and ill gives him the desire to send her money and to travel to China to see her. He is unable to do either because the dispute with his tenant prevents him from putting his house up for sale to raise money, circumstances which add greatly to his despair. However, even in this predicament he keeps his sense of humour, as Lynne Curran records: “Li, in court to try to resolve the muddle created by “the lodger”, when they pronounced his name wrongly: “Your name is Mr Li.” He answered, “No you are Mr Liar.” He decides that the desire to live in a country not one’s own is ‘stupid’. His sole good fortune was to discover the arts because you can gain knowledge of arts ‘as you wish and be self-taught.” After his mother’s death, he turns back in earnest to his work.

1991-1994

Li engages simultaneously on several strands of work. Photography: he experiments with superimposition (including ‘see-through’ photographs of his own paintings and sculpture), with colour-printing and hand-colouring of black and white prints; with ‘still-lives’ and other set-ups for the camera, both in daylight and by candle-light, in the house, in the garden, the local landscape, and a large tank of water with goldfish installed in one of the outbuildings.

Photography is also the medium for a series of disturbing self-images with his face covered or hidden, a genre unlike anything Li had produced before. Sculpture: Li salvages a large number of off-cut timber pieces from local sawmills, which become like human surrogates or stand-ins in a long series of photographed groups. Also, he makes scores of impromptu sculptures: groupings of pieces of wood, stones, flowers, etc. around the house, merging into ‘still-life’. Smaller pieces of wood are planed down on one side as tablets for chiselled inscriptions in Chinese, usually Confucian sayings and proverbs concerning ethics and behaviour, sometimes bitter, sometimes hopeful. Reliefs: Li paints monochrome reliefs incorporating photographs and Chinese inscriptions on moveable panels. Poems: Li continues to produce short poems as a vehicle both for his disillusionment with human affairs and his rapturous identification with the cosmos.

Believing he still has much to do, Li ignores for as long as possible the signs of approaching illness.

November 1994

Li dies at the Eden Vale Hospice in Carlisle of intestinal cancer. He is buried at Lanercost Priory in the valley below Banks, with both an Anglican and a Chinese ceremony at the graveside. His grave in Lanercost cemetery is marked by a tall stone inscribed with his Time-Life-Space emblem carved in local red sandstone by his friend the sculptor & letter cutter Bryant Fedden.