Biography

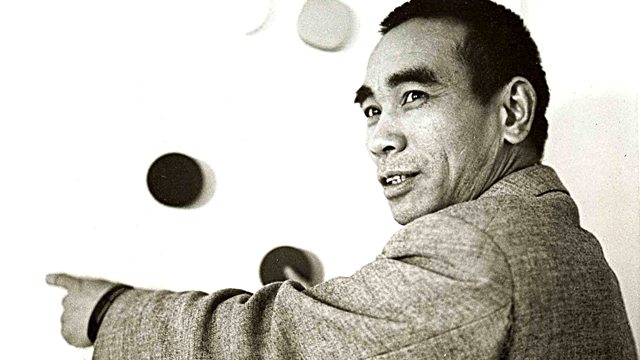

An artist, curator, poet and archivist, Li Yuan-chia ranks among the most original and radical of post-war artists. Born in south China in 1929, Li Yuan-chia studied art in Taiwan where he is considered to have been one of the founding fathers of Chinese abstract painting in the 1950s. Travelling from Taiwan to Italy and then to England, he arrived in London in 1965 to exhibit at Signals gallery and later showed with the Lisson Gallery. After leaving London in 1968, he spent the remainder of his life in Cumbria in northern England where he established the LYC Museum and Art Gallery in his own home. As well as opening his home and giving exhibitions to over 300 artists in a ten-year period, Li continue to be innovative in his own art work and his poetry. He also continued to evolve his artistic language which was based in the notion of the “Cosmic Point”. This took many forms, some purely visual, others participatory. For Li, the Point was “the origin and end of creation”. He gave it form according to a most refined artistic and poetic sensibility.

Li dared to be simple. Throughout his life he tried to make his thought as accessible to others as he could. Its beauty is inseparable from its simplicity. Yet he was aware of the paradox involved in this too, for he said, “ The simpler a thing is, the more likely it is to be misinterpreted or even dismissed. This tiny dot can mean all or nothing to you.” In other words, its simplicity demands an act of identification, communication even, from the spectator, and all art, like life, is a dialogue in the face of an abyss.

The ‘tiny dot’ was Li’s great visual invention. It was the physical and metaphysical emblem of his art. He called it the Cosmic Point, the mark which conjures up infinite space, the beginning and end of all things. At the same time it was the ‘me’, Li Yuan-Chia, on my individual life journey. It was also ‘you’, the viewer who brings to it your subjective charge.

Despite his lack of official recognition, and his independent way of doing things, Li was not a self-absorbed or maverick figure. His concerns were central ones in the 20th century avant-garde. What is the value of art, what is it for, who is an artist? Can art give an account of our place in the universe? Can it help us to live? Li was constantly reflecting on questions such as these, in both his visual art and his writing. He was a “visual philosopher”, as Sheldon Williams aptly remarked in the 1960. He was also a man who experienced and suffered. How to tell the story of the objective and subjective sides of Li? His life seems to lead towards a melancholy end if one considers the tragic predicament in which he found himself in his last years. Anger and despair is reflected in his extraordinary late work. But so is happiness and beauty. In fact many kinds of contrary: optimism and pessimism, joy and misery, conviviality and loneliness, articulation and muteness, spirituality and materiality, seemed to accompany Li all through his life, and to become its real drama.

Guy Brett